The family Phrynichidae

Euphrynicus bacillifer female

Damon annulatipes male

Identification and anatomy

The family Phrynichidae consists of middle-sized species like Phrynichodamon scullyi (20 mm), species belonging to the genus Damon of eastern Africa (24-30 mm), Trichodamon (20-28 mm) as well as species of great size like species of the genus Damon from western Africa (30-35 mm), some Phrynichus species (up to 35 mm) and Euphrynichus species (up to 36 mm).

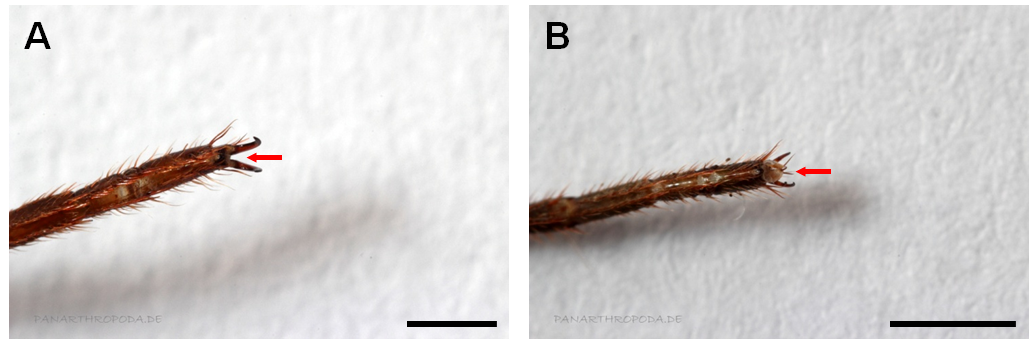

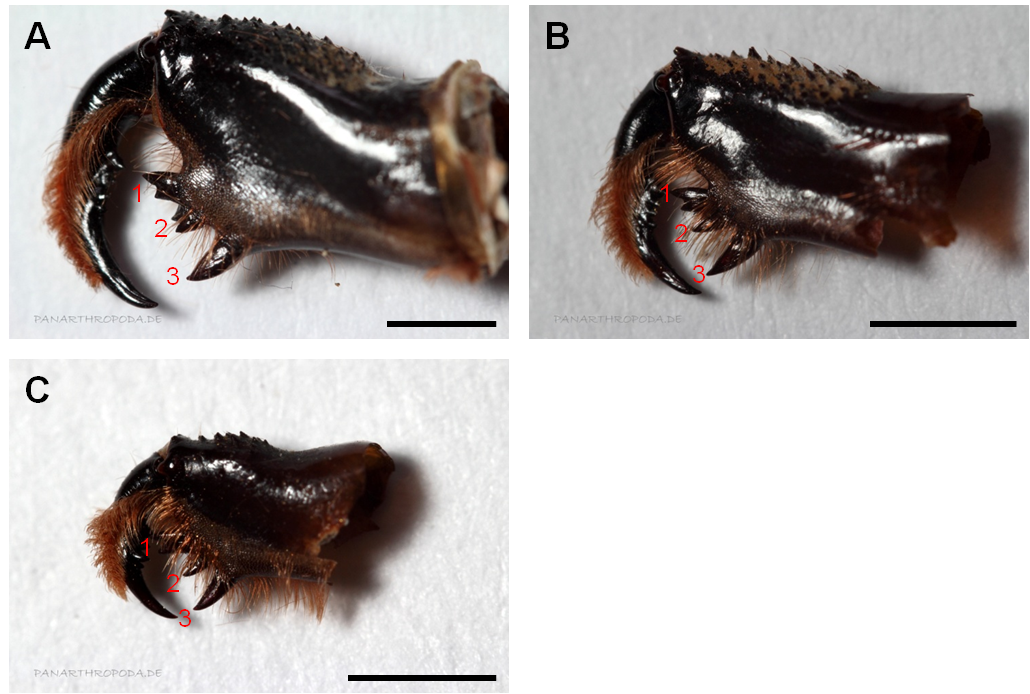

The family Phrynichidae as part of the grouping of the Apulvilata can morphologically be distinguished from the genus Paracharon, the family Charinidae and Charontidae by the lack of Pulvilli (Figure 1, A) on the tarsi of the walking legs and the presence of three denticles in the inner denticle row of the chelicerae (Figure 2) (Weygoldt, 2000).

Figure 1: Ventral view of walking-leg tarsi with and without pulvilli. A) Tarsus without pulvillus of Euphrynichus bacillifer (Phrynichidae), B) Tarsus with pulvillus of Charon grayi (Charontidae). The red arrow indicates the part of the walking leg where a pulvillus can be found in species that are not belonging to the Apulvillata. Scale bar 2 mm

Figure 2: Chelicerae of representatives of three genera belonging to the Phrynichidae. A) Phrynichus orientalis, B) Euphrynichus bacillifer, C) Damon diadema. The red numbers indicate the different denticles of the inner denticle row of the cherlicera. Denticle 1 is bicuspidate where the upper cusp is the greater one in all representatives of the family Phrynichidae except Xerophrynus (Weygoldt, 2000). A) The depicted denticle 2 is not bicuspidate, this impression results from an additional denticle that is located behind the level of the denticle row. To simplify the depicturing of the denticle rows fringe hairs were (partially) removed. Scale bar 2 mm

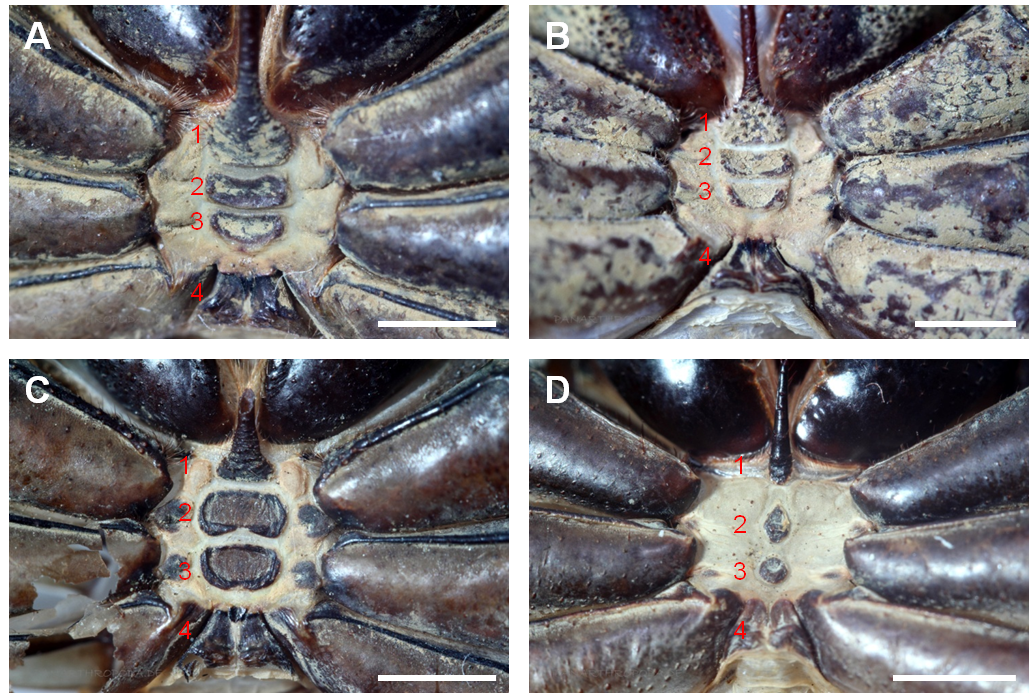

The Phrynichidae can be distinguished from the Phrynidae by the occurrence of broadened second and third prosomal sternites that cover a major part of the intercoxal area (Figure 3, A-C). In the Phrynidae these sternites are reduced to small tubercles (Figure 3, D) (Weygoldt, 2000). In the Phrynidae the female genitals possess claw-like sclerites which is not the case in the Phrynichidae (an exception is the Phrynichid Damon uncinatus) (Weygoldt, 2000).

Figure 3: Prosomal sternites of three representatives of the Phrynidae and one representative of the Phrynidae. A) Phrynichus orientalis (Phrynichidae), B) Euphrynichus bacillifer (Phrynichidae), C) Damon diadema (Phrynichidae), D) Phrynus goesii (Phrynidae). The red numbers indicate the prosomal sternites. In the Phrynidae the two median prosomal sternites (2, 3) are broadened and cover a major part of the ventral intercoxal area (A-C). In the Phrynidae (and the remaining families of the order Amblypygi) the two median prosomal sternites are reduced to small tubercles (D). Scale bar 2 mm

A characteristic trait of the family Phrynichidae (Xerophrynus excluded) is a change in the arrangement and number of spines on the pedipalps during postembryonic growth which leads to the formation of a prehensile hand (Weygoldt, 2000). The first free living instars exhibit the three primary dorsal spines of the pedipalp tibia which are of equal length and characteristic for the most species belonging to the Neoamblypygi (Charontidae, Phrynidae, Phrynichidae) (Weygoldt, 2000) . In case of representatives of the Phrynichidae the pattern and number of these spines changes during growth. The first two dorsal spines (counted beginning distally) of the pedipalp tibia come closer and shift to the distal end of the pedipalp tibia. The third dorsal spine is reduced in most species or even disappears totally as it is the case in some species. In many species most spines on the pedipalp femur and tibia are reduced or lost during postembryonic growth (Weygoldt, 2000). Together with the ventral spines I and II of the pedipalp tibia and the tarsus a characteristic prehensile hand (phrynichid hand) is formed that functions in a distinct other way than the catching basket of the representatives of other families (Weygoldt, 2000). So in the Phrynidae prey is catched by a grasping movement of the prehensile hands which differs from the clasp knife like movement by which prey is cached in the other families of the amblypygid using their armatured pedipalp tibia and femur.

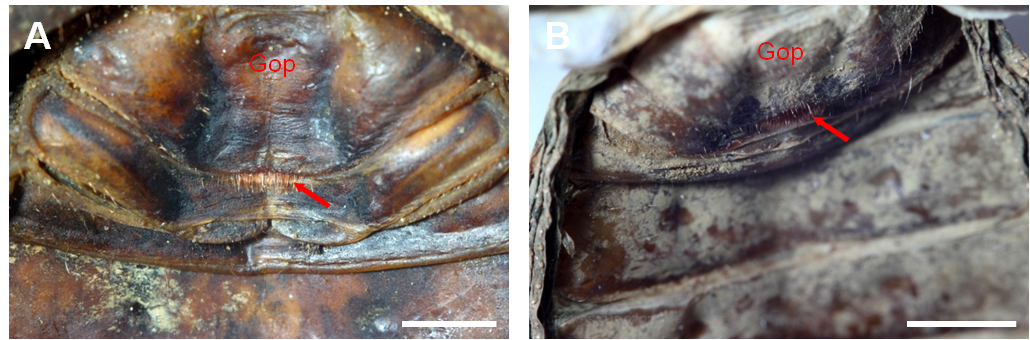

The differentiation of the different sexes can easily be achieved in many representatives of the Phrynichidae. Females of these species posses red fringe hairs on the posterior margin of the genital operculum (Figure 4) (Weygoldt, 2000).

Figure 4: Ventral view of the anterior part of the opisthosoma of female representatives of the Phrynichidae. A) Phrynichus orientalis, B) Euphrynichus bacillifer. The red arrows indicate the red fringe hairs on the posterior margin of the genital operculum (Gop) by which a specimen can be identified as female. Scale bar 2 mm.

Distribution

The family Phrynichidae occurs in Africa and Asia, solely the genus Trichodamon can be found in South America. The genera Phrynichodamon, Damon, Musicodamon and Euphrynichus (E. bacillifer can also be found in Madagascar) occur only in Africa.

The genus Phrynichus occurs in the Palaeotropics. This genus can be found in continental Africa, the Seychelles, Madagascar, the Arabian Peninsula, India and Sri Lanka and the Far East like Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia (Weygoldt, 2000).

It is supposed that a major part of the adaptive radiation of the Phrynichidae occurred preceding the separation of the Gondwana land masses and that the present geographical distribution of the Phrynidae and the genus Trichodamon in South America and that of the Phrynichidae in Africa and Asia is due to the separation of South America and Africa. Hence the occurrence of the genus Trichodamon in South America could be a relic of a former broader distribution of the family Phrynichidae in this part of the world.

Another possibility could be that Trichodamon reached South America by rafting on driftwood (Weygoldt, 2000). The genus Damon has undergone an extensive adaptive radiation in Africa (Prendini et al., 2005; Weygoldt, 2000). The African genera Xerophrynus (whose inclusion in the Phrynichidae is not clear),Phrynichodamon and Musicodamon are monotypic (Weygoldt, 2000).

Inner systematics

The family Phrynichidae consists of the genera Xerophrynus, Phrynichodamon, Damon, Musicodamon, Trichodamon, Phrynichus und Euphrynichus. The genus Xerophrynus forms the sister grouping of the remaining groupings within the Phrynichidae or is treated as sister grouping of the grouping of the Phrynichidae itself (Weygoldt, 2000).

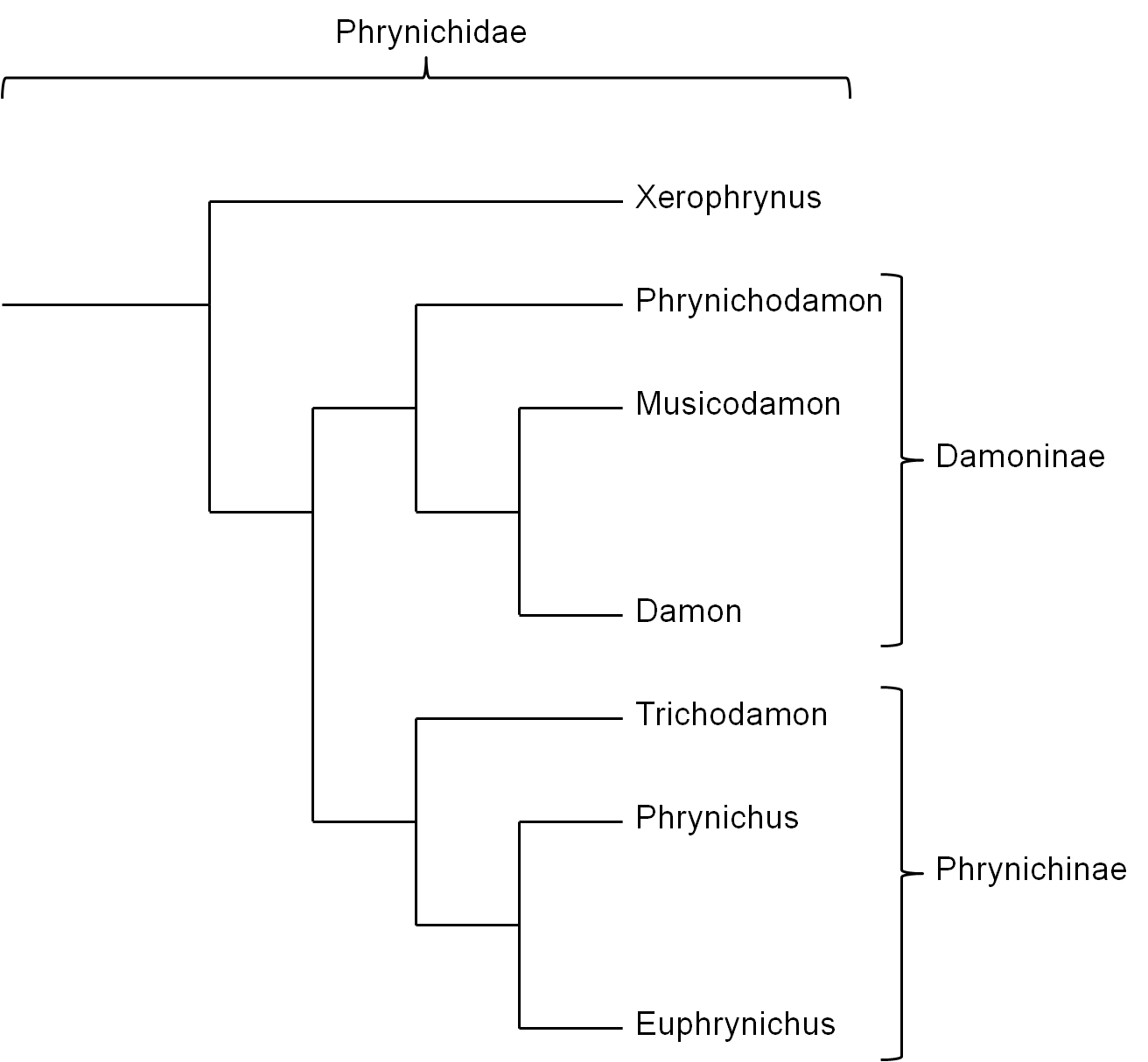

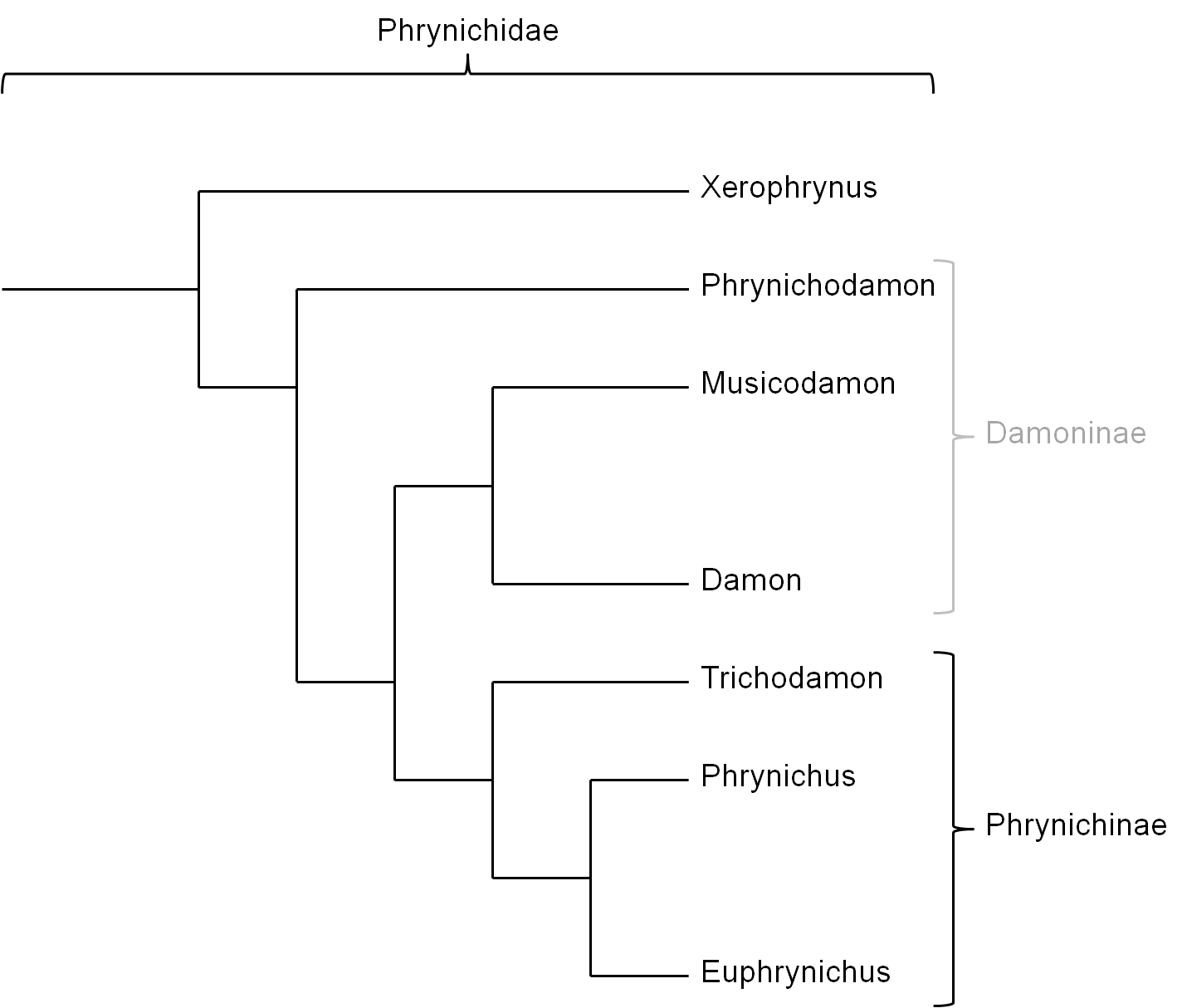

Traditionally the family Phrynichidae is separated in two subfamilies (Figure 5): i)Damoninae which groups the genera Phrynichodamon, Damon and Musicodamon and ii) Phrynichinae which groups the genera Trichodamon, Phrynichus and Euphrynichus (Weygoldt, 2000). This classification is uncertain taking account of that it is most likely that the subfamily Damoninae forms a paraphylum (Figure 6) because the phylogenetic relations of Musicodamon and Phrynichodamon with the other groupings is relatively uncertain (Weygoldt, 2000; Weygoldt, 2002).

Due to the relatively complex spermatophores of Musicodamon, which resembles the spermatophores of the genus Trichodamon it has been assumed that Musicodamon is part of a monophyletic grouping consisting of this genus and the Phrynichinae by exclusion of the remaining Damoninae (Weygoldt, 2000).

An alternative explanation could be that the complex spermatophores are a synapomorphic trait within the Phrynichidae, which groups the genera Damon, Musicodamon and the Phrynichinae in a monophylum with the exclusion of Phrynichodamon (Figure 6). Less complex spermatophores within the genus Damon would be a result of a secondary simplification which likely did not take place in D. uncinatus (The spermatophore of D. uncinatus is not known but the female genitals suggest that the spermatophores of this species is of a certain complexity).

Respecting these findings D. uncinatus could form the sister taxon of a grouping of the remaining species of the genus Damon (Weygoldt, 2002). Consequently the subfamily Damoninae would have to be abandoned because Phrynichodamon with its spermatophores and female genitalia of low complexity would form the sister grouping of the Phrynichidae with complex or secondarily simplified spermatophores (Weygoldt, 2002).

New findings that include genetic analysis render possible a grouping of the Phrynichidae (Xerophrynus excluded) in Damoninae and Euphryninae in which the relatively simple spermatophores and female genitals of Phrynichodamon are also a result of secondary simplification of more complex forms that occurred in the ancestor of Phrynichodamon and Musicodamon (Figure 5) (Prendini et al., 2005).

Figure 5: Relationships between the genera Phrynichidae with classical division in the subfamilies Damoninae and Phrynichinae. Xerophrynus forms the sister grouping of the remaining grouping in the Phrynidae (Weygoldt, 2000). Background for the grouping of Phrynichodamon in the subfamily Damoninae is the assumption that the relatively simple spermatophores and female genitalia in this species as in many representatives of the genus Damon are a result of a secondary simplification (Weygoldt, 2002). From this point of view complex spermatophores and female genitalia are a symplesiomorphic trait of the whole family Phrynichidae (Prendini et al., 2005; Weygoldt, 2002).

Figure 5: Relationships between the genera Phrynichidae with classical division in the subfamilies Damoninae and Phrynichinae. Xerophrynus forms the sister grouping of the remaining grouping in the Phrynidae (Weygoldt, 2000). Background for the grouping of Phrynichodamon in the subfamily Damoninae is the assumption that the relatively simple spermatophores and female genitalia in this species as in many representatives of the genus Damon are a result of a secondary simplification (Weygoldt, 2002). From this point of view complex spermatophores and female genitalia are a symplesiomorphic trait of the whole family Phrynichidae (Prendini et al., 2005; Weygoldt, 2002).

Figure 6: Relationships between the genera of the Phrynichidae with the subfamily Damoninae as a paraphyletic grouping. Background for the exclusion of the genus Phrynichodamon from the Damoninae, which in this case become paraphyletic, is the assumption that the relatively simple spermatophores and genitalia of Phrynichodamon are not a derived trait but plesiomorphic. In this case complex spermatophores and female genitalia in Musicodamon, Damon (often secondarily simplified) and the Phrynichinae are a synapomorphic trait within the Phrynichidae (Weygoldt, 2002).

The grey depiction of “Damoninae” represents the paraphyly of this grouping on the assumption of the shown phylogenetic relationships.

References

Prendini, L. (2005). Systematics of the group of African whip spiders (Chelicerata: Amblypygi): Evidence from behaviour, morphology and DNA. Organisms Diversity & Evolution, 5, 203-236.

Weygoldt, P. (2000). Whips Spiders (Chelicerata: Amblypygi). Their Biology, Morphology and Systematics. Apollo Books, Stenstrup, DK.

Weygoldt, P. (2002). Fighting, Courtship, and Spermatophore Morphology of the Whip Spider Musicodamon atlanteus Fage, 1939 (Phrynichidae) (Chelicerata, Amblypygi). Zoologischer Anzeiger - A Journal of Comparative Zoology, 241, 245-254.

F. Schramm, authored 2011